Sustainability and climate risk: what can banks expect?

The growing importance of sustainability issues and the role of credit institutions in financing transformation places climate and environmental risks at the core of regulatory and supervisory scrutiny today. For some years now, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS), comprising central banks and national supervisory authorities, has been working to enhance sustainability and climate risk awareness in the financial sector. This approach involves promoting shared best practices, including providing climate scenarios for central banks and supervisors in environmental and climate risk management.

Recently, major banking supervisors, including the European Central Bank (ECB), Bank of France and Bank of England, have set out new expectations and developed requirements which, in 2022, will see the first European climate stress test run by the ECB take place.

In parallel, there are ongoing global efforts to develop, clarify and harmonise disclosure requirements to make sure everyone speaks the same language and avoid greenwashing.

Regulatory expectations and disclosure requirements

All major regulators have declared an interest in environmental issues and have recently put pressure on financial institutions to make sure they integrate such risks into their respective risk management practices. The French Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority (ACPR) conducted its first climate stress test in 2020, and the ECB plans its first EU-wide climate stress test in 2022. In 2021 the ECB asked a large sample of European banks to conduct a self-assessment exercise related to climate and environmental risks and test results against the regulatory expectations described in the ECB guide published in November 2020. In addition, the banks were asked to submit their plans explaining how and when they will be in line with ECB expectations. Based on feedback received, the ECB published a report in November 2021 on the state of climate-related and environmental risk management in the banking sector. Due to the current regulatory focus on climate and environmental risk management, banks are likely to see a gradation of increasing requirements, ranging from awareness to potentially a capital charge in the future.

Where are we today?

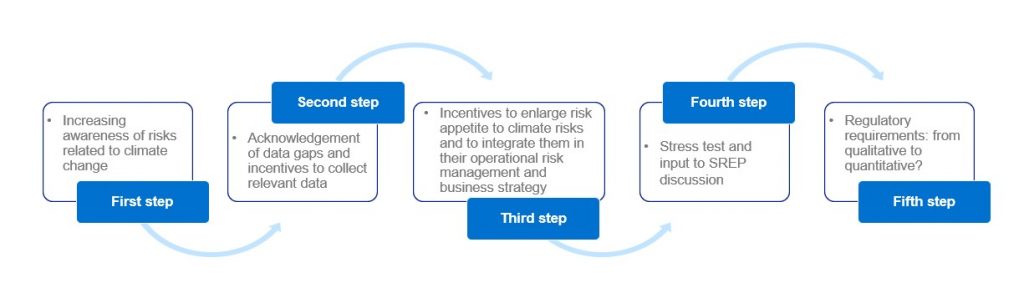

In terms of supervisory dialogue, we are currently between the third and the fourth step, as shown in the diagram. As the ECB and national regulators have made their expectations clear through specific feedback in autumn 2021 and have provided some benchmarking, banks are now expected to have identified any shortcomings and data gaps and are taking steps to correct them.

It is particularly important to define clearly the banks’ understanding of definitions and coverage of climate and environmental risks. It is also essential to recognise and document the anticipated impact of these risks on the business environment in which the banks operate. At the same time, banks need to differentiate between physical risks, transition and responsibility risks and take them into account when defining the business strategy. In concrete terms, banks have to integrate those risks within their risk appetite and, like all other risks, manage to navigate them along the different business lines. Banks should also adapt their governance to ensure risks are managed at the appropriate organisational level and across the three lines of defence. Finally, these risks should be consolidated in internal reporting systems and reported to the management bodies and relevant committees.

At this stage, the ECB has noted that EU banks have begun to integrate some of those risks in their respective risk appetite and risk management frameworks. This is true for the more easily manageable environmental risks such as phasing out the financing of activities highly exposed to climate-related risks, financing coal or systematically evaluating real estate collateral towards climate risks. However, banks struggle to integrate climate risk exposure in existing credit, market and liquidity risk management operations and in internal reporting systems. For the latter in particular, few banks seem to have developed specific risk indicators. Therefore, the ECB pressure is likely to increase in 2022 with the outcome of stress tests included in the context of Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) discussions.

Currently, only qualitative assessment requirements are expected. Nevertheless, as the Bank of England has already mentioned, capital discussions will follow shortly. However, this will not come before consultations take place as the solution is not obvious due to a time horizon that is quite different from traditional risk timelines. For example, how are regulators going to cope with the very long-term horizon of those risks? Also, will future regulation seek to have a higher capital charge on non-green activities or have a lower capital charge on green financing as an incentive? While these are open questions today, banks should be prepared to confront them.

Multiple new sustainability reporting requirements across Europe

Just as critical as moving the sustainability agenda across all industries is the need to improve the quality and relevance of sustainability reporting significantly, as there cannot be sound risk analysis and monitoring without robust and reliable data at the outset. This was identified as a key driver of an effective sustainable finance strategy by the EU back in 2018 and since then has led to a mushrooming of global initiatives.

In its 2018 Action Plan on Financing Sustainable Growth, the European Commission (EC) structured its whole sustainable finance strategy around three key objectives; reorienting capital flows towards a more sustainable economy, mainstreaming sustainability in risk management, and fostering transparency and long-termism.

Each of these three objectives led to the adoption of several new regulations and legislations in the EU. Some prompted the review and amendment of existing prudential and regulatory requirements for financial institutions, such as MiFID II, Solvency II, CRD and DDA directives. All had in common the creation of new sustainability reporting obligations.

Significant new reporting obligations

Three cornerstone texts creating significant immediate or near-term new sustainability reporting obligations for financial institutions in line with the above three key objectives. These include the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) adopted in late 2019. The SFDR targets financial market participants and aims to enhance the integration of sustainability risks in investment policies and compensation policies, foster transparency on the principal adverse impacts of investments on the environment, society and governance practices, and on sustainability characteristics and objectives of so-called ESG products. Therefore, it requires financial market participants to disclose related information at entity and product levels in various places and documents. This includes websites, pre-contractual and contractual documents, and periodic reports. Implementation was phased in, starting in March 2021 until 1 July 2022, when all requirements will come into force.

The Taxonomy regulation, also called the green taxonomy, adopted in June 2020, establishes a classification of “green” or sustainable activities and will significantly and rapidly contribute to Europe’ sustainability agenda if performed according to demanding environmental performance conditions. Today, it only covers the climate change objectives of mitigation and adaptation. By the end of 2022, it will aim to cover all six environmental goals, including biodiversity, circular economy, water resources and pollution. The purpose is to provide financial institutions with science-based tools to make informed investment decisions on environmentally-friendly activities, projects and industries, thus contributing to financing sustainable growth, as announced in the 2018 Action Plan.

All entities in scope of the taxonomy regulation, which includes all large Public Interest Entities (PIEs) and financial institutions, will have to publish the amount of turnover, capex and opex generated by taxonomy-aligned activities in their periodic report. For banks, it means reporting their Green Asset Ratio (GAR), which is the share of their assets that finance sustainable or green activities as defined by the taxonomy. Banking supervisory authorities will closely monitor GAR at national and EU levels. Implementation will start as early as 2022, progressively ramping up to reach full disclosure mode in 2024.

Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) aims to standardise sustainability reporting on an equal footing with financial reporting. If adopted by the European Council and Parliament, the CSRD proposal will impose mandatory reporting requirements on all listed and large companies in the EU, including financial institutions. These requirements will cover all aspects of the ESG spectrum and the obligation to have sustainability reports audited by independent reviewers.

By creating a reliable, common sustainability language, based on clearly defined disclosures, and imposing high-quality sustainability reports that are independently reviewed, the CSRD should help streamline and refocus the reporting exercise and enhance relevance and usefulness of data provided to the users of sustainability information, starting with investors and banks. If adopted by mid-2022 as expected, the CSRD would come into force in 2024 for reporting year 2023[1].

International initiatives gaining momentum

In the wake of the leading European efforts, international players have also gathered momentum. Two recent moves that will require scrutiny in the next few months include the consolidation of SASB, IIRC and CDSB into the Value Reporting Foundation, which will pursue an investor approach to continue developing sector-specific standards of voluntary use by international companies. Also, the creation of an International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) alongside the IASB will help support initiatives. The ISSB’s recently appointed Chair confirmed that it will discuss and adopt its work program for the coming years in 2022 and will aim to adopt the final version of its first two prototypes on general presentation and climate-related disclosure by the end of 2022.

Both organisations have the support of the investor community because their approach to sustainability gives priority to valuable information for decision making, including elements that have consequences on the entity’s financial performance, also called financial materiality. The European approach gives equal importance to information relating to the entity’s impacts on its ecosystem. Such impact materiality is also important to other stakeholders.

However, they currently remain voluntary standards. So, the question is: will they be endorsed and made mandatory by some countries and when? Most likely not before the European effort is fully operational and implemented throughout Europe. Therefore, it is probable that Europe will continue to lead the way in sustainability reporting for some time.

The good news is that as the investor-focused international approach is a sub-part of the European approach, they are not contradictory and should largely overlap. This avoids the trap of multiple reporting obligations, which is good news for preparers and users of sustainability information alike.

[1] Based on current discussions in EU Parliament and Council, a one-year delay in implementation is highly likely. First time application of CSRD would then be 2025 on reporting year 2024.

Financial services tax digest – October 2025

As we enter the final quarter of 2025, political instability and limited growth continue to affect the global economy. However, promising market opportunities are emerging. Banks, insurers and asset managers must be prepared to navigate efficiently in an evolving domestic and cross-border tax environment. In this October edition of the Financial Services Tax Digest, experts […]

Exploring IFRS 18: what insurers need to know

IFRS 18 – Presentation and disclosure in financial statements is set to replace the IAS 1 – Presentation of financial statements and will be effective for the period beginning on 1 January 2027. IFRS 18 applies to all entities, including insurance companies. For insurance companies, IFRS 18 follows a series of transformative accounting standard milestones. While IFRS […]

Interview with Sylvie Matherat, Global Senior Adviser at Forvis Mazars, on the finalisation of Basel III

Conducted by David Ciolfi, Senior Manager, Forvis Mazars RegCentre On 12 May 2025, the Basel Committee issued a landmark statement reaffirming its commitment to finalise the full implementation of Basel III in all jurisdictions “in full and consistently and as soon as possible”[1]. This position comes amid growing tensions between the ambition for a globally […]

EUROFI 2025 reflections: regulatory simplification as a competitiveness imperative in a fragmenting global environment

Eric Cloutier, Partner, Forvis Mazars Group, took part in the EUFORI panel in September 2025 on ‘Simplifying EU banking regulation and supervision; priorities and next steps’. The session was moderated by John Berrigan, Director-General at DG FISMA, with esteemed panellists including senior policymakers and supervisors such as José Manuel Campa (Chairperson, EBA), Nathalie Aufauvre (Secretary […]

Channelling sustainable finance in APAC: overcoming fragmentation and navigating towards inclusion

A snapshot of the sustainable finance landscape in APAC In spite of a slowdown in the APAC sustainable finance market in 2025, momentum remains strong in key pockets. Sovereign issuances are setting the tone for private sector participation and strong local currency markets are bolstering domestic growth, encouraging the participation of APAC’s growing ecosystem of […]

Quarterly economic update for the financial services sector

Insights from George Lagarias, Chief Economist, Forvis Mazars Economics Hub. The financial services sector is poised for growth due to deregulation and lower interest rates, enabling banks to expand loan books and recapture market share from private investors. However, global economic challenges, including trade wars, persistent inflation and high debt levels, cloud the outlook. Risks […]

Financial services tax digest – June 2025

As the saying goes, “the only constant in life is change.” As we enter the third quarter of 2025, global economic uncertainty continues to escalate. President Trump’s pause on “reciprocal” tariffs is set to expire on 8 July 2025. Currently, the U.S. has only reached trade deals with the UK and China. However, negotiations with […]

Artificial intelligence in the EU financial sector – balancing regulation and innovation

To harness the potential benefits of AI safely, financial institutions must ensure that they have appropriate guardrails in place to allow safe innovation. The EU’s AI Act will help shape how institutions govern artificial Intelligence across functions. Boards must focus on ensuring that AI risks are identified and addressed across the development, procurement and use […]

Sanctions compliance in Europe: navigating complexity with confidence

Sanctions compliance has rapidly evolved from a niche area of regulatory focus into a critical and high-risk concern for financial services firms. As geopolitical tensions rise and sanctions regimes become more expansive and ever changeable, firms operating across borders must navigate an increasingly fragmented and high-stakes landscape. In advance of the launch of Forvis Mazars’ […]

Managing ESG and climate risks: rising supervisory expectations for financial institutions in the UK and EU

As ESG and climate risks climb the supervisory agenda, financial institutions face rising expectations from both UK and EU regulators. This article compares the evolving approaches of the PRA and EBA—and what firms must do now to stay ahead. In the past six months, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) and the European Banking Authority (EBA) […]

Bridging the capital markets integration gap: an operational framework for a supervisory efficiency test

Europe’s capital markets are increasingly integrated — but supervision remains fragmented. Without a more coherent supervisory model, regulatory arbitrage and inefficiencies will grow. A new approach is needed. The EU’s financial market supervision remains fragmented and misaligned with the depth of market integration achieved through initiatives such as the Capital Markets Union (CMU) and the […]

Measuring climate risk exposure with a flexible and readable metric: carbon beta

The reform of the Solvency II Directive, set to be enforced no later than January 30, 2027, introduces new sustainability-related risk requirements. These include (i) the creation of transition plans with quantifiable goals and processes to monitor and address financial risks from sustainability factors in the short, medium, and long term and (ii) an assessment […]

Beyond the baseline: addressing tail risk in Expected Credit Loss models

A follow-up to our previous analysis In our previous article – Navigating the new trade war: implications on Expected Credit losses – we explored the rise in provisioning needs triggered by both direct impacts (sector/geography-specific exposure to tariffs) and indirect impacts (macroeconomic degradation influencing model parameters). Through simulations and stress testing, we showed how seemingly […]

Financial services: navigating the new trade war

Political background Since early 2025, under President Donald Trump’s second term, the United States has escalated tariff actions on a wide array of imports, reigniting global trade tensions. A series of key announcements* has introduced significant volatility into financial markets: *This context is accurate as of 10 April 2025. However, given the extreme pace of […]

Putting people at the heart of sustainability: interview with Simon Rawson – Executive Director, The Taskforce on Inequality and Social-related Financial Disclosures

In an exclusive interview with Forvis Mazars, Simon Rawson, Executive Director, The Taskforce on Inequality and Social-related Financial Disclosures (TISFD) discusses the work, objectives and approach of the taskforce. Simon explains how the taskforce is about creating a knowledge base, evidence and recommendations on a social-related disclosure framework that could be used for businesses to […]

Financial services tax digest- April 2025

As Benjamin Franklin famously said, nothing is certain in this world except death and taxes. As we enter the second quarter of 2025, we find great uncertainty – and tax is at the heart of it. The prospect of an international tariff war looms. Although financial services businesses are not expected to be the primary […]

Financial services regulatory landscape in APAC: navigating the complexities and emerging trends

In 2025, the financial services landscape in the Asia-Pacific (APAC) region continues to experience rapid and structural change driven by complex and interconnected risks. These elements are fundamentally reshaping regulatory priorities across the region, prompting diverse responses from national authorities. The region’s vast diversity can lead to regulatory fragmentation, requiring financial institutions to navigate a […]

Understanding DORA compliance and regulatory expectations for financial institutions

The DORA (Digital Operational Resilience Act) regulation came into force across the financial sector on 17 January 2025. Unsurprisingly, only a small number of firms affected by DORA have declared themselves completely ready and compliant with all areas of the regulation. The European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) have affirmed their position on the minimum requirements firms […]

Deregulatory pressures to encourage competitiveness and growth: there is no such thing as a free lunch

This article was written in collaboration between our Forvis Mazars Economics Hub and Forvis Mazars Global Financial Services Regulatory Centre. In the aftermath of the 2008 Global Financial Crisis (GFC), stringent regulations were developed for the banking and insurance sector to prevent the need for future public bailouts during times of financial stress. Nearly two […]

Single Resolution Board (SRB) 2025 work programme

On 2 December 2024, The Single Resolution Board (SRB) published its work programme for 2025. The Programme sets out the SRB’s main priorities for the next year, alongside the continued and important work on standard operations. An overarching priority is to streamline the resolution planning process and resolution plans to make them more efficient and […]

European Securities and Market Authority (ESMA) strategic priorities for 2025

On 1 October 2024, ESMA published its strategic priorities for 2025: ESMA’s annual work programme. The strategic priorities for this year build on the five-year ESMA strategy for 2023 to 2028, focusing on fulfilling ESMA’s mandates in legislation and expanding upon activities from 2023 and 2024. ESMA’s 2025 strategic priorities are outlined are three strategic […]

European Central Bank (ECB) supervisory priorities for 2025-2027

On 18 December 2024, The European Central Bank (ECB) published its supervisory priorities for 2025-2027, which reflect the Bank’s medium-term strategy. Forvis Mazars interviewed Patrick Montagner, member of the ECB Supervisory Board, to discuss the ECB’s supervisory priorities for 2025-2027 and the 2025 stress test. The conversation highlights how the ECB is adapting its supervisory […]

European Banking Authority (EBA) 2025 work programme

On 2 October 2024, the European Banking Authority (EBA) outlined its work programme for 2025, focusing on the continued implementation of the EU banking package (Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR) III / Capital Requirements Directive VI) and the enhancement of the Single Rulebook, which was also a priority in 2024. Additionally, the EBA will take on […]

Basel Committee work programme and strategic priorities for 2025/2026

The Basel Committee work programme for 2025/2026 outlines the strategic priorities for its policy, supervisory and implementation activities for the two-year period. The key themes of the committee’s 2025-2026 work programme include: The work programme builds on its mandate to strengthen the regulation, supervision and practices of banks worldwide with the purpose of enhancing global financial […]

European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) 2025 work programme

The European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) published its 2025 work programme which is embedded in its revised single programme document 2025-2027. The year 2025 marks the start of this three-year plan. EIOPA’s mission is to protect the public interest by contributing to stability in the short, medium and long term. This mission is […]

EU Cloud: can Europe manage to create an attractive alternative?

Sovereignty raises debate and there is a wide divergence in the way to deal with that topic. The current debate in Europe on the EU Cloud Services (EUCS) High+ criteria is an illustration of the diverse positions existing in that field. Addressing sovereignty as an isolated concept does not make sense. Sovereignty should be addressed […]

ECB interview: 2025-2027 ECB supervisory priorities and 2025 stress test

In this exclusive interview by Forvis Mazars, Patrick Montagner, member of the ECB Supervisory Board, discusses the ECB’s supervisory priorities for 2025-2027 and the 2025 stress test. The conversation highlights how the ECB is adapting its supervisory focus and practices to address the evolving risks faced by the banks it supervises, including geopolitical shocks, climate […]

Financial services tax digest- January 2025

As we say goodbye to 2024 and look forward positively to 2025, at Forvis Mazars we know that financial institutions and funds will have to deliver in an evolving complex domestic and/or cross-border tax environment. Banks, insurers and asset managers all over the world may have to capture M&A opportunities and/or deal with some efficient […]

Latest NGFS climate risk scenarios: Implications for financial institutions

In November 2024, the Network for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) released the latest version (termed Phase V) of its climate risk scenarios. These introduce significant advancements that enhance financial institutions’ accuracy when undertaking climate-related financial risk assessments. Key advancements include the incorporation of a new damage function for physical risk assessment, the integration of […]

Assessing climate risk for the insurance industry: How reliable are climate scenarios?

As the impacts of climate risks become more pronounced, regulators and the insurance industry are under increasing pressure to refine risk assessment frameworks. This article examines regulatory developments, a critical review of climate scenarios and limitations of models within the insurance sector, the implications of new regulatory developments, and the role of actuaries in establishing […]

The rising importance of risk culture in banking supervision

In the wake of financial crises, the question ‘Where was the board?’ has become a rallying cry, reflecting the demand for greater accountability within banking institutions. Recent high-profile bank collapses underscore the necessity of robust internal governance frameworks that include a strong risk culture at their core. Supervisors worldwide continue to elevate risk culture as […]

Top risks facing financial services firms in 2025: key highlights

As part of our annual series on “Top risks facing financial service (FS) firms”, we have identified and ranked the key risks for financial services business leaders in 2025. We discuss in the article below the top five areas that FS firms should prioritise in 2025. Our more detailed assessment can be found here, which contains […]

Reflections on the Africa Financial Summit: adapting to global shifts in risks and regulations

Forvis Mazars proudly participated in the Africa Financial Summit (AFIS) 2024, held from 9-10 December in Casablanca, Morocco, and sponsored the awards ceremony. Below are some reflections on the state of play and future of Africa’s financial sector. In recent years, the world has undergone dramatic changes, challenging the status quo in unprecedented ways. This […]

NGFS phase V climate risk scenarios: good progress however unaddressed limitations remain

In November 2024, the NGFS[1] (Network for Greening the Financial System) published phase V of its widely used climate scenarios updated with the most recent economic and climate data, policy commitments, and model versions. This phase V also introduces a new damage function for physical risk assessment. The new damage function incorporates various climate variables […]

Industry Cloud Platforms: Unlocking innovation through tailored cloud solutions

Cloud computing has been with us for over 15 years, but we have barely scratched the surface of its potential.[1] Industry Cloud Platforms (ICPs) are cloud-based solutions targeting the specific needs of industry verticals that generic and traditional solutions do not adequately address. These solutions encompass cloud services, applications and data models tailored to meet […]

Financial reporting of European banks: towards the end of the “golden age” of post-model adjustments (PMAs) / overlays to banks’ expected credit losses (ECL)?

When the Covid-19 pandemic broke out in 2020, the banks had to make post-model adjustments[1] (or management overlays) to incorporate the impact of this unprecedented situation into the expected credit losses recognised by the banks. While the end of the pandemic should have put an end to these exceptional adjustments, the events that followed (war […]

Financial reporting of European banks: an overview of expected credit losses indicators against a backdrop of continuing uncertainty in YE 2023

After several years of significant macroeconomic and geopolitical events such as the Covid-19 crisis, the war in Ukraine, the return of inflation and rising interest rates, the year 2023 seemed to mark a form of stabilisation in the international environment in the absence of any notable new event, despite the continuing uncertainties. How has the […]

Understanding the impact and future of the DORA regulation

The European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) published the final texts of the DORA (Digital Operational Resilience Act) regulation in July. These definitive texts will come into effect in January 2025, enhancing digital operational resilience and IT risk management for all financial entities. Key takeaways from the final DORA regulation texts In July, the European Supervisory Authorities […]

What to know: Global FS sustainability disclosure requirements

A day doesn’t seem to go by without there being another sustainability regulation announcement. This article is a whistle-stop tour around selected jurisdictions and provides an update on what has happened in the past few months, what is to come, and what these developments mean for firms. In summary, reporting on sustainability issues is growing […]

New international principles to strengthen third-party risk management by banks

In the ongoing digitalisation of the banking sector and the rapid growth of financial technology, banks increasingly rely on third-party service providers (TPSPs), including for some of their critical functions. This dependency introduces significant risks, as banks do not always have direct control over these external entities. These risks are further exacerbated by cyber threats, […]

How can AI driven solutions aid AMLA in curbing money laundering?

Traditional methods of tackling financial crime are no longer effective in a world where bad actors use increasingly sophisticated techniques to exploit weaknesses in financial crime controls. With the establishment of a new European regulator, embedding the latest AI-enabled solutions to counter financial crime is of utmost importance. The formation of the Anti-Money Laundering and […]

Adapting regulations to the fast-paced world of crypto assets

In today’s dynamic financial landscape, cryptocurrencies and their underlying technology have taken centre stage, attracting both enthusiasts and sceptics. The volatility and potential of digital assets prompt questions about their evolving positions in the traditional financial market. While the promise of decentralisation sparks innovation, ongoing debates on regulation, security, and stability keep the narrative of […]

Ukraine’s reconstruction: challenges and opportunities

On 24 February 2024, Ukraine and the rest of the world marked the second anniversary of Russia’s invasion. Despite extensive media coverage of the war and its geopolitical and socio-economic ramifications on Europe and the rest of the world, there is an opportunity for investors to explore the potential in Ukraine. This article aims […]

Identifying and managing the ethical risks of AI in financial services

The role of artificial intelligence (AI) in financial services continues to exercise C-suite minds. Not least, how to balance AI’s benefits to enhance the customer experience and improve back-office operations with the ethical challenges that AI presents. Sparking the debate is how financial organisations can employ AI tools such as machine learning (ML), large language […]

Using emerging technology to support ESG and sustainability reporting

The financial services sector is increasingly looking to technology to help tackle the rising levels of regulation they face. According to the latest Forvis Mazars C-Suite Barometer, the prominence of new technology as a global trend is on the rise in financial services, making it one of the most important issues now topping the C-Suite […]

Developing a technology talent strategy

As financial services organisations increasingly focus on digital transformation, having the right expertise and skillsets is critical. However, it’s not simply a question of human capital. It requires developing a talent strategy that recognises the profound impact technology will have across the organisation. Technologies such as cloud, containers, artificial intelligence and machine learning, internet of […]

Mapping digital transformation in financial services

Digital transformation now tops the C-Suite agenda of financial services organisations. According to the latest Forvis Mazars C-Suite Barometer, one-third of respondents identified the need to transform company IT as a strategic priority ahead of issues such as sustainability initiatives. While the competitive landscape has been evolving for several years following the arrival of digital-first challenger […]

Managing confidence and optimism in financial services

Optimism in the financial services sector is riding high. According to the latest Forvis-Mazars C-Suite Barometer, 94% of financial services respondents say they’re growing, which is five points higher than the global average and up overall from 92% last year. At the same time, 97% of leaders in financial services predict growth in 2024, up […]

Challenges in governance – managing the ever increasing complexity

In the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis, regulators and legislators around the world tried to make sense of its causes and then implement rules to stop it happening again. In the UK, the resulting regulation introduced by the Financial Conduct Authority, FCA, was the Senior Managers Certification Regime, which in its current state, carries […]

Navigating regulatory waters: a comprehensive look at recent developments in the financial sector

In the dynamic world of finance, regulatory updates play a pivotal role in shaping industry practices and safeguarding the interests of stakeholders. From strengthening anti-money laundering measures to fostering transparency in crypto-asset markets, recent months have witnessed a flurry of regulatory activity across various domains. In this comprehensive overview, we delve into the intricate details […]

Operational resilience: where do we stand and what does this mean for cross-border banks?

Operational resilience is the ability of firms to prepare for, prevent, adapt and respond to, recover and learn from operational disruption. It is a complex and multi-faceted challenge for cross-border banks to prepare for and respond to. This is because potential causes of operational failure can enter a firm from several directions and their impacts […]

Basel 3 implementation: what is still at stake?

An EU vs UK vs US perspective Sixteen years ago, the collapse of Lehman Brothers triggered the global financial crisis, which highlighted significant weaknesses in the global banking sector. The oversight of the sector was quite fragmented between jurisdictions, leading to inadequacies in regulation and supervision. In response, the Basel Committee, which sets global standards […]

AMLA: what challenges may it face and what lessons can be learnt from other jurisdictions

Differing approaches to Anti-Money Laundering (AML) and Counter-Terrorist Financing (CTF) supervision across the EU have severely limited member countries’ ability to fight efficiently this growing threat. The creation of the Anti-Money Laundering and Countering the Financing of Terrorism Authority (AMLA) is a huge step in addressing this issue. AMLA will be charged with i) supervising […]

The pressure is on EU banks to rapidly improve their risk data capabilities

Following the 2007-08 global financial crisis, substantial deficiencies were identified in many banks’ risk data aggregation capabilities and risk reporting practices globally. This impacts banks’ ability to make timely risk decisions, creating risks not only for themselves but for the stability of the global financial systems. The Basel Committee responded by developing in 2013 the […]

Maximise the value of the Cloud with FinOps: a guide to optimising Cloud costs

Financial institutions are faced with several challenges: strong economic pressure, regulatory changes, evolving customer expectations, punctuated by strong competition from fintechs and insurtechs; which rely natively on emerging technologies to offer best-in-class services. To meet these challenges and stand out from fintechs and insurtechs, financial services (FS) companies have invested massively in move-to-Cloud strategies, rapidly […]

Reinforcement learning in financial companies: reconciling performance and ethics

Reinforcement Learning (RL) is a branch of Machine Learning (ML) that is still little known to the general public. In this approach, an agent repeats actions and, depending on the result of these actions, receives a reward or punishment in the form of a score. Focussed on maximising the score, the agent adapts the next […]

Bridging borders by combatting illicit financial flows and corruption for global financial integrity

Africa’s economic potential is hindered by the pervasive presence of illicit financial flows (IFFs), fraud, and corruption, which not only strip the continent of vital resources but also obstruct its path towards sustainable development. The staggering annual loss of $88.6 billion to IFFs, as reported by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), […]

Strengthening global collaboration for asset confiscation and seizure: dynamics and innovations

In the ongoing battle against financial crimes spanning money laundering, terrorist financing, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, collaborative efforts in asset confiscation and seizure stand as vital bulwarks. As we navigate the complexities of the financial landscape in 2024, recent advancements, particularly within the European Union (EU), underscore the critical importance of […]

Our top risks for financial services firms in 2024

We have identified and ranked the key risks for financial services business leaders in 2024 based on market research, regulatory insights as well as our assessment of the current difficulties facing firms. We discuss in this article the key takeaways for you and your organisation. A more detailed assessment can be found here, which contains […]

Our top risks for financial services firms in 2024 – complete analysis

We have identified and ranked the key risks for financial services business leaders in 2024 based on market research, regulatory insights as well as our assessment of the current difficulties facing firms. We also highlight the changes in risk rankings compared to last year, justified by global events and new regulations that have surfaced in […]

Unlocking the potential of ecosystems: a deep dive into open insurance and APIs

In the contemporary landscape of insurance, the business model of open insurance, characterised by the strategic opening of insurers’ resources to external collaborators, has been a focal point of discussion. Unlike the banking sector, where regulatory mandates such as the Payment Services Directive (PSD2) of 2018 have compelled the development of open banking practices, insurers […]

Being an Independent Non-Executive Director in different jurisdictions: lessons learned from Mazars in Ireland roundtable

Mazars recently hosted a Financial Services INED Roundtable Dining Event in Dublin[1]. Over 50 financial services independent non-executive directors (INEDs) attended, from banking, asset management, funds and insurance entities operating across the EU and UK. The roundtable focussed on the challenges facing INEDs in the current unpredictable macroeconomic environment. The new and emerging risks and […]

Navigating challenges in the retail digital euro landscape

Last October, the European Central Bank (ECB) initiated the preparation phase of the Digital Euro project, following two years of investigation and a proposal on the establishment of a digital euro published by the European Parliament (EP) in June 2023. In January, the ECB began seeking potential providers to develop a digital euro platform and infrastructure […]

The European Central Bank’s priorities for 2024: where do we stand after the first quarter?

The European Central Bank (ECB) issued the SSM supervisory priorities for the 2024-2026 cycle on 19 December 2023. They sum up what institutions under the direct supervision of the ECB should expect in terms of areas of supervision, in 2024 notably, and allow firms to prepare themselves for forthcoming onsite inspections or thematic reviews. Please […]

Unveiling the European Central Bank’s strategy: data, scenarios and models

In January 2024, the European Central Bank (ECB) published its Climate and Nature Plan for 2024-2025. This plan aims to: This plan underscores those financial risks stemming from climate change remain a key area of attention for the ECB. The ECB will continue working on several topics including stress testing, scenarios and climate-related data, and […]

Drafting the future: unveiling the next chapter of DORA

DORA is a legislative proposal that aims to improve the digital operational resilience and ensure the performance and stability of the financial system of the member countries of the European Union in the face of the risks associated with ICT (Information and Communication Technology) in the financial sector (cyber-threats, cyber-attacks). The DORA requirements will apply […]

How banks and insurers have progressed in embedding sustainability into their businesses

In late 2023, and to coincide with COP 28, Mazars published its latest Sustainability practices survey on the progress banks and insurers have made in embedding sustainability into their businesses, our most comprehensive and information-rich report to date covering 404 executives in banks and insurance companies in 16 countries. Despite sustainability being in the limelight […]

SRB annual conference 2024: entering a new phase of banks testing and operationalisation of resolution plans

The Single Resolution Board (SRB) convened its annual conference on 13 February 2024 with a theme highlighting the focus for the year: ‘The road ahead: risk, readiness and resilience’. While significant strides have been made with the EU banking resolution framework and tools, the SRB’s Chair Dominique Laboureix recalled this is not the end of […]

Assessing materiality and verification of sustainability disclosures

In environmental, social and governance (ESG) reporting, materiality is crucial for enhancing transparency and accountability in sustainability and climate-related disclosures. Importantly, it helps identify and report on matters that are deemed significant, emphasizing their relevance to stakeholders. Materiality comes in various forms. Financial materiality focuses on sustainability issues impacting financial performance, aligning with annual financial […]

What’s driving financial firms’ sustainability strategies?

To adapt to the swiftly evolving regulatory landscape and meet stakeholders’ expectations, financial firms are increasingly formulating sustainability strategies to address environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors. Notably, emissions reduction and the pursuit of net-zero targets have become central elements of ESG strategies for many financial firms, according to the latest Mazars’ survey Sustainability practices stocktake: […]

Market in crypto assets regulation: where we stand now

On 29 June 2023, the European Union’s (EU) Markets in Crypto Assets Regulation (MiCA) entered into force. It is being implemented in stages depending on the provisions, between June and December 2024. The regulation, which provides clearer rules for crypto-asset service providers and token issuers, is much needed for this fast-changing industry. The rapidly approaching […]

Mitigating the financial impacts of climate-related risks

The integration of environmental, social and governance (ESG) considerations into strategic planning is increasingly becoming a common practice among financial services firms. However, climate-related risks can also serve as drivers of financial risk for institutions. These risks can manifest through various transmission channels, translating climate and environmental (C&E) risks into more conventional categories such as […]

How are financial institutions reflecting C&E considerations in risk appetite statements?

There is growing pressure for banks and insurers to incorporate C&E factors in their risk management frameworks (RMF). As a practice, it gives the ability to set clear thresholds for the climate impacts banks and insurers are willing and able to absorb. By establishing these thresholds, firms can effectively monitor their exposure to C&E risks, […]

Adapting governance to spearhead sustainability more effectively

There are increasing regulatory expectations globally for financial institutions to disclose and demonstrate how sustainability-related responsibilities are allocated within the organisation. In this respect, the increasing global trend towards mandatory sustainability disclosure frameworks continues to underscore the significant role that the finance function is anticipated to assume in sustainability. It’s a trend reflected in Mazars’ […]

SSM supervisory priorities for 2024-2026: addressing identified vulnerabilities in banks

On 19 December 2023, the European Central Bank (ECB) published its updated Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) strategic supervisory priorities for the period 2024 to 2026. The priorities indicate what banks should expect in terms of supervisory activities in 2024. For 2024-2026, the ECB supervisory priorities are built upon three main pillars: These priorities were informed […]

How financial institutions can move sustainability reporting to real-world application

The increased demand for sustainable finance shows that awareness of environmental, social and governance (ESG) issues is generally high among financial institutions. Indeed, for many of the larger players subject to the EU’s Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD), there has been a requirement to include ESG information in annual reports for some time. Others have incorporated […]

Managing tomorrow’s banking risks

While the banking sector has shown resilience over recent years, the economic environment and geopolitical situation remain tense. So, what does this mean for risks to the banking sector? More specifically, what is the impact on capital requirements for banks with the implementation of the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR3) and the Capital Requirements Directive (CRD6), […]

Lessons from the spring 2023 banking turmoil: five areas for banks to focus their attention

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) and Financial Stability Board (FSB) published reports in October 2023 on the causes and lessons learnt from the Spring 2023 banking turmoil. The BCBS report provides an assessment of the causes of the banking turmoil, the regulatory and supervisory responses, and the initial lessons learnt. The FSB report […]

European green taxonomy eligibility ratios in the banking sector

The implementation of the European Union’s ‘Taxonomy’ regulation, which integrates two climate objectives, was carried out on 1 January 2022 through the ‘Climate’ Delegated Act released in April 2021. In line with this, the banking sector has been provided with corresponding regulations, allowing banks to measure the portion of their financing dedicated to sustainable economic […]

Transitioning to greener practices in the real estate sector

In 2022, the European Union implemented the green taxonomy for the second year, requiring companies to disclose indicators related to climate objectives. The green taxonomy aims to guide capital investment towards environmentally sustainable activities, making companies assess their alignment with the EU’s sustainable transition and enabling financial institutions to prioritise funding for projects contributing the […]

Eligibility ratios in the insurance sector: improved practices based on recommendations issued by regulators

2023 marks the second year in which insurance and reinsurance companies have published their eligibility ratios for the European Green Taxonomy. For the insurance sector, the objective is to measure the proportion of investments, as well as the proportion of gross premiums collected in non-life insurance, dedicated to financing economic activities in accordance with the […]

IIF annual membership meeting: building resilience amid turbulence and transformation

The IIF Annual Membership meeting is a setting for insights and perspectives from global financial regulators and senior financial sector executives on topical economic and regulatory issues. Being a forum with global coverage means that it is a valuable setting for picking up future economic and regulatory directions. A packed agenda under the theme of Building […]

DORA: how to move from operational risk management to operational resilience?

DORA (the Digital Operational Resilience Act) is the key regulatory outlook for IT and Cyber risk between now and 2025. The European Supervisory Agencies have sought to strengthen the resilience of institutions by emphasising the need to evolve the approach to operational risk management, of which information and communication technology risks are a part. DORA […]

Diversity in forward-looking macroeconomic scenarios

Under IFRS 9, forward-looking information is a key component of Expected Credit Loss (ECL) calculations. However, forward-looking information requires a significant level of judgement, making comparisons difficult to navigate. Indeed, similar to the use of post-model adjustments, forward-looking scenarios have also been reported by stakeholders in the context of the IFRS 9 impairment post-implementation review […]

Bank credit risk trends show a relative decrease in high risk exposures

Despite banks emerging from the Covid-19 crisis in reasonably good health, the war in Ukraine combined with a global energy crisis and an uncertain economic landscape have once again put the spotlight on credit risk exposures. To better understand credit risk trends, Mazars conducted an analysis of 26 banks in 11 European countries in May […]

The use of post-model adjustments to capture emerging risks

Since the Covid-19 pandemic, post-model adjustments1, or management overlays, have become an increasingly common and accepted mechanism used by banks to manage expected credit losses (ECLs). The number of post-Covid unprecedented events related to the war in Ukraine, energy crisis and global economic uncertainty has raised a number of questions relating to the consistency and […]

Equipping NEDs to challenge private investment valuations

A recent major board reshuffle in one of Europe’s largest listed investment companies has focused attention on private investment valuations. It follows concerns raised by an ex-director over the robustness of the directors’ processes for approving investment valuations. The issues primarily question whether the Board of Directors has sufficient training and experience and whether governance […]

EU bodies update country lists of uncooperative and high-risk countries for financial services

Revised list of uncooperative countries and territories for tax purposes published by the European Council The list of uncooperative countries and territories about tax is an important part of the external tax strategy of the EU. Globally, this strategy intends to contribute to the ongoing efforts to advance good governance practices in the tax domain. […]

New reports on transaction monitoring systems and risk analysis published by the ACPR and COLB

ACPR publishes report on automated AML/CFT transaction monitoring systems In 2022, the ACPR conducted a comprehensive thematic review, focussed on the automated systems utilised by the entities under its supervision. This entails entities implementing their obligations in terms of transaction monitoring. The primary objective of this review was to assess the efficiency of the operation and […]

EUROFI financial forum: strengthening economic union and European competitiveness

The Eurofi financial forum is a setting for exchanges between European Union (EU) economic and financial regulators and senior financial sector executives from the industry. It occurs bi-annually alongside the Economic and Financial Affairs Council configuration (ECOFIN) meetings. This summary takes stock of the Eurofi discussions, as well as recent publications by the EU Commission […]

The Council of Europe provides updates on combatting the financing of terrorism

2022 AML-CFT Committee report available The MONEYVAL Committee, an entity of the Council of Europe which is tasked with addressing challenge of money laundering and terrorist financing (ML/FT), has recently published the AML-CFT report 2022. The findings of the report are primarily centred around adherence to compliance with global sanctions, notably in freezing or confiscation […]

EU regulatory framework on the establishment of the digital euro: from investigation to realisation

With the approaching end of the investigation phase of the ECB’s digital euro project in October 2023, and the expectance of a decision on starting a realisation phase by the end of this year, the pros and cons of a potential digital euro have been widely discussed in the past months. The topic became even […]

The EBA publishes new report and guidelines in response to risk within the financial services sector

New report on AML/CFT risks in payment institutions In accordance with the European Union regulations, the European Banking Authority (EBA) has been mandated to assess the management of the most significant risks in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing (ML/FT). The entity’s analysis is centred around the identification and management of ML-FT risks […]

The European Parliament devises a new agreement to restrict access and abuse of financial services information

New measures to combat money laundering and terrorist financing The European Parliament has adopted a set of stringent measures to strengthen the fight against money laundering and terror financing, alongside circumventing sanctions within EU. These regulations are presented by EU in the form of a “legislative package” comprising three key measures which provide various practical […]

Asset managers and ESG implementation: turning regulatory and operational compliance into commercial opportunities

ESG-related regulatory requirements, and scrutiny, show no signs of abating. Asset managers have a pivotal role in financing the transition towards low-carbon economic systems. Hence, governments have introduced several ESG-related regulatory requirements that apply to asset managers. Some examples of these are the Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) in the EU and the mandatory disclosures […]

Basel reforms: similarities and divergences between the UK and EU

Both the UK and the EU are consulting on the next wave of iterations to the Basel reforms. Whilst the focus of these consultations has been relatively broad, the rules around the computation of Pillar one Credit Risk RWAs have seen the most significant change. This article outlines some of the main differences between the […]

European Commission to strengthen regulatory framework for bank crisis management

The European Commission published on 18 April 2023 a new legislative package aiming to adapt and strengthen the framework for crisis management and deposit insurance (CMDI), with an acute focus on small and medium-sized banks. This proposal, which follows the announcement of the Eurogroup finance ministers inviting the Commission and the European co-legislators to review […]

Greater insight into the AMF certification exam, the AMF-ACPR report and ROSA

On 16 December 2022, the AMF published additional information[1] on its website about the AMF exam, more commonly known as the “AMF certification” exam, since it certifies only the entities that organise the exam, rather than the people who pass it. The AMF lists the various functions within ISPs and FIAs that are covered by […]

How does the 2023 Finance Act provide clarification on tax-favoured schemes and extend their validity?

The tax system applicable in the overseas public authorities includes a set of investment incentive schemes designed to promote their economic and social development. One factor to their successful implementation in practice is to provide as much visibility and sustainability for an investor as possible over time. Another key is to have a broad scope […]

ESMA’s latest Q&A: which key topics are covered and how has it impacted the AFG?

The European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) published on 17 November, together with EBA and IOEPA, a Q&A on the RTS of the SFDR Delegated Regulation (Commission Delegated Regulation (EU) 2022/1288), just six weeks before coming into force. The Q&A clarifies a number of points, including those relating to principal adverse impacts (PAIs) and taxonomic […]

What lessons can be drawn from recent events in the banking sector?

In recent weeks, we have witnessed the successive bankruptcies of three banks in the United States, as well as the hasty takeover of Credit Suisse by UBS. This chain of events inevitably calls into question whether this trajectory echoes the leadup to the financial crisis of 2008. In reality, whilst these crises have stark similarities, […]

New DORA regulation: the challenge for insurers to strengthen their IT and cyber risk management

Since the onset of 2023, regulatory news has been adorned with the latest European legislation, under the acronym DORA, adopted on 10 November 2022 by the European Parliament. Standing for the Digital Operational Resilience Act, it will apply to the members of the European Union from 2025, and concerns companies in the financial sector specifically. […]

Sustainable finance series: Why does sustainable finance matter?

The momentum towards a low-carbon economic system is only set to grow. Financial services firms are pivotal actors in the transition; consequently, increasing demands are being put on them to demonstrate their sustainable finance activities and credentials. This blog explains what sustainable finance is and why it matters to financial services firms. What is Sustainable […]

Sustainable finance series: Driving credible ESG actions

Implementing credible environmental, social and governance (ESG) actions requires successful enablers. So how can firms identify these enablers and, crucially, remove barriers to implementation? If we take our latest C-Suite Sustainability Barometer, we can see that out of the over 1,100 businesses accounted for in the survey, 75% are planning to increase their investment in […]

The digital euro as we know it today

“I see digital as the future of finance”. These are the words of the Executive Vice President of the European Commission (EC), Valdis Dombrovskis, voiced in the summer of 2020. He has undoubtedly been proven right as governments and central banks around the world have heightened their efforts to keep oversight of the digital transition […]

Climate change valuation adjustment: introducing a climate change scenario extrapolation to long dated CDS curve

The global climate crisis has triggered the financial sphere to address the way in which it conducts business. Climate risk consideration is currently growing in the banking industry but should also be considered by banks in the Credit Valuation Adjustment (CVA) when pricing derivatives. The credit risk for long dated derivatives (beyond 10 years), reflected […]

The Fed shares instructions on its first pilot climate scenario analysis exercise

The Federal Reserve Board (Fed) has shared instructions on its pilot climate scenario analysis exercise (CSA). Six of the largest U.S. banks, i.e., Bank of America, Citigroup, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley, and Wells Fargo are participating in the exercise and are requested to submit their results along with documentation by July 31, 2023. […]

Why ESG-linked features impact financial assets classification under IFRS?

In our last article on sustainability-linked financing, we highlighted the accounting issues related to these contracts that are currently being debated between stakeholders. The most critical issue is the classification of loans or bonds that reference the borrower or issuer’s environmental, social and governance (ESG) key performance indicators (KPIs) on the balance sheet of lenders […]

Spotlight on main European banks’ credit risk

After two years marked by the Covid-19 crisis, the first half of 2022 offered the prospect of a return to a certain economic normality. However, the outbreak of war in Ukraine combined with a deteriorating economic environment have reshuffled the cards and once again brought banks into a zone of turbulence and uncertainty. So how […]

COP27: stepping up implementation and the role of finance

A lot of attention at COP27 was focused on the likelihood of keeping global warming to 1.5 °C, in line with the goals of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement. The consensus was that we are in real danger of falling off track. Few nations revised their nationally determined contributions to reduce their carbon footprint compared […]

Results of the ECB 2022 thematic review on climate-related and environmental risks

The European Central Bank (ECB) has expressed a significant supervisory concern surrounding more than half of supervised banks in terms of the progress made on fulfilling the expectations specified in the Guide on climate-related and environmental risks. The ECB recently concluded its 2022 thematic review of the banking sector’s alignment with supervisory expectations. This review […]

EBA considers bottom-up stress testing with top-down elements

The European Banking Authority (EBA) is tasked, in cooperation with the European Systematic Risk Board (ESRB), to initiate and coordinate biennial EU-wide stress testing exercises to assess the resilience of institutions to adverse market developments. The objective is to provide supervisors, banks, and other market participants with a common analytical framework to consistently compare and […]

IFRS series on sustainability-linked financing

As environmental, social and governance concerns are becoming more and more prevalent, sustainable finance is now under the spotlight. The financial sector has a key role to play in achieving the ESG transition. One of the levies developed by the financial industry is to propose new kinds of financing that promote ESG practices and projects […]

Green taxonomy trends facing the real estate sector

The European Union (EU) has taken the first step in directing capital investments toward so-called sustainable activities with the introduction of the Green Taxonomy on 1 January 2022. For the real estate sector, the objective is to measure the share of eligible activities contributing to the first two climate objectives – the mitigation of climate […]

Can BIS develop a cryptoasset regulatory framework without limiting the innovation process?

In summer 2022, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) published its second consultation paper on the prudential treatment of cryptoasset exposures. The guidelines outlined in the proposed document follow an initial discussion paper released in 2019 and a first consultative document issued in 2021. The complete text is set up as a new standard to […]

The FED announced a pilot climate scenario analysis exercise for early 2023

The Federal Reserve Board (FED) will commence its first bottom-up climate scenario analysis exercise at the beginning of 2023, as announced on 29 September. The exercise will be exploratory in nature and will not result in extra capital requirements. The list of designated participants consists of six of the largest U.S. banks, i.e., Bank of […]

Reliable information key to the insurance sector’s ability to apply Green Taxonomy

The objective of the European Union’s Taxonomy regulation, in force since 1 January 2022, is twofold for the insurance and reinsurance sector. First, to measure the share of investments devoted to financing economic activities eligible for the taxonomy, known as the Investment Ratio. Second, to measure the share of gross premiums written in eligible non-life […]

Banks grapple with GAR objectives

In force since 1 January 2022, the European Union’s Taxonomy regulation aims to support the market for green finance. More specifically, greater transparency in the market will help prevent greenwashing by providing information to investors about the environmental performance of assets and economic activities of financial and non-financial information. For the banking sector, the target […]

New pilot scheme opens pathway for blockchain technology

A new regulation introducing a pilot scheme based on blockchain technology is set to come into force on 23 March 2023. The new European regulation1 is an experiment to develop secondary markets for financial securities based on distributed ledger technology (DLT). Authorised participants in the scheme will be able to provide trading services and settlement-delivery […]

Results of the ECB 2022 climate risk stress test

The first supervisory climate risk stress test (2022 CST) conducted by the European Central Bank (ECB) has concluded with official results and findings made public on 8 July 2022. The exercise has complemented the broader ECB’s agenda to assess the readiness of banks in Europe to manage climate-related and environmental risks. The 2022 CST was […]

Russian sanctions: what implications for financial institutions?

Following Russia’s annexation of Crimea in March 2014, the United States (US) and the European Union (EU), together with other countries, imposed mainly economic sanctions on Russia. Since Russia’s recognition of the self-proclaimed autonomous republics of Donetsk and Lugansk, followed by Russia’s attack on Ukraine on 24 February 2022, these sanctions have taken on new […]

How to address climate risk in the banking prudential framework

Climate change is now firmly in the focus of prudential regulators and supervisors across the globe. Against this background, the European Banking Authority (EBA) is mandated to assess whether a dedicated prudential treatment of exposures related to assets or activities associated substantially with environmental and social objectives would be justified. Based on its findings, the […]

Quarterly SSM briefing: stable supervisory priorities and the ECB’s green agenda

The last few weeks have been marked by an ongoing review of the supervisory priorities initially listed by the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) for 2022-24, and developments in the climate agenda outlined by the European Central Bank (ECB). ECB’s supervisory priorities for 2022-24 remain stable despite geopolitical instabilities and challenges At the beginning of 2022, […]

The return of inflation: what consequences for banks?

For several months now, we have been in an economic and financial environment that we have not seen for some years. In May, inflation in the Eurozone reached 8.1%, with six countries exceeding 10%, while the United States recorded an 8.6% year-on-year price increase. The short-term reasons for the return of inflation are well known, […]

Real estate share deals: survey and assessment from a tax perspective

The years between 1848 and 1918 are considered the relevant building period for the Gründerzeit-Zinshaus buildings in Vienna. In this period Viennese housing construction underwent a decisive development which shaped the city’s characteristic flair to this day: the Zinshaus buildings – so typical for Vienna – came into existence. Viennese Gründerzeit-Zinshaus buildings have not lost […]

France steps up sustainable transformation with mission-led business law

France’s innovative and incentivising Action Plan for Business Growth and Transformation (PACTE) law lays the legal foundations for corporate social responsibility. With more than 400 companies established as “sociétés à mission” – mission-led businesses – by the end of 2021, this new scheme is an undeniable success. The number of mission-led companies has doubled in […]

The digital euro: the future of central banking in Europe?

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) continue to receive increasing attention not only from the ECB but all over the world. So far, 10 countries [1] have already deployed CBDC programmes with another 15 countries [2] currently conducting pilot programmes. In total, 105 countries are considering using CBDC programmes, representing over 95% of global GDP and […]

Leveraged transactions: supervisory expectations in the Eurozone

The chair of the European Central Bank’s Supervisory Board, Andrea Enria, has voiced several times in the past months the supervisor’s concern with the increasing growth of the leveraged finance sector, which deals with loans to highly indebted borrowers. By mid-2021, the combination of a strong global loan moratoria policy and the long-standing low interest […]

Impacts and consequences of the war in Ukraine for banks and insurance companies

The war in Ukraine, as well as the unprecedented sanctions imposed by the European Union, the United States and their partners against Russia have had major consequences for financial services institutions. For foreign companies operating in Russia or Ukraine, the first concern was the safety of their staff. They had to make difficult choices to […]

Solvency II Directive measures to aid European economic recovery

While the European Commission’s most recent opinion on the review of the Solvency II Directive is broadly in line with the final European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIPOA) opinion issued in December 2020, some measures have now been amended. These amendments are designed to strengthen the capacity of European insurers to contribute to the […]

New-style cyber insurance policy models on the rise

Regardless of geography or business sector, many groups and companies have taken out cybersecurity insurance policies in recent years. These policies cover companies against new threats to information systems, including ransomware and data theft incidents that have been making the headlines. For a long time, the risks identified in these policies were on the borderline […]

Sustainable finance regulations signal a sea change for insurance sector

The European Green Deal aims to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 and create a modern, competitive and resource-efficient economy. To meet its objectives, the European Commission has begun to restructure the non-financial reporting requirements for companies. Although some of the requirements were partially implemented in 2021, this is only the beginning of a real sea […]

European crisis management framework: ripe for reform?

Since the European crisis management framework was established in 2014, there have not been many failing banks in Europe. However, the recent global health pandemic, combined with the ongoing conflict in Europe between Russia and Ukraine, could easily change this. The EU crisis management framework was established in response to the global financial crisis and […]

Can markets in crypto-assets (MiCA) give banks a regulatory edge?

Crypto-asset markets have been on banks’ radar for some time. While interest and involvement have varied, regulatory developments have been a driving force. In September 2020, the European Union (EU) published a proposal for the regulation of Markets in Crypto-assets (MiCA), offering a uniform legal framework for crypto-assets in the EU. On 14 March 2022, […]

Eurofi financial summit addresses EU’s ecological and digital transition

As a setting for exchange between European Union (EU) economic and financial regulators and senior financial sector executives from the industry, one of the world’s largest financial services conferences, Eurofi, took place in Paris in February. Established in 2000, the Eurofi meetings occur bi-annually* alongside the Economic and Financial Affairs Council configuration (ECOFIN) meetings. The […]

Banks need to step up efforts on climate and environmental risk disclosures

In March 2022, the European Central Bank (ECB) published its second snapshot of climate-related and environmental risk disclosure levels among significant institutions under its direct supervision. In line with the results of the first snapshot published in November 2020 – regarded as the baseline measurement – none of the institutions in scope for this second […]

Prudential risks for banks with a Russian presence

The invasion of Ukraine by Russia on 24 February 2022 is considered the most significant geopolitical event since the Second World War. While there is no question of military intervention by the European Union (EU) at the moment, the EU has nevertheless decided on a major package of sanctions that will have a heavy impact […]

EBA launches a central database for AML/CFT

A central database to strengthen the anti-money laundering and counter-terrorist financing (AML/CFT) framework was launched by the European Banking Authority (EBA) on 31 January 2022. Called EuReCA, the new database will be essential to coordinate efforts by national competent authorities and the EBA to prevent and fight money laundering and terrorist financing (ML/TF) risks throughout […]

GDPR has controls over subcontractors in its line of fire

Like all industries, the real estate sector has to implement a range of legal, technical and organisational measures to protect the personal data of its employees, customers, prospects and suppliers. Processing must comply with several regulations related to data protection, including, for example, the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), applicable since 25 May 2018. Same […]

Embarking on an ambitious common climate framework

As part of the European Green Deal, the European Union intends to encourage green investments and prioritise the revision of the Non-Financial Reporting Directive (NFRD). The European or Green Taxonomy, which sets out a precise classification of sustainable activities with the strategic objective of redirecting capital flows towards those activities from 2022, is a result […]

Fast close implications for real estate management companies

The market is seeing a growing trend for real estate management companies seeking to speed up the process of closing their accounts. This is largely due to the positioning of real estate funds in life insurance contracts requiring increasingly shorter valuation intervals. Furthermore, as the regulatory obligation to publish Net Asset Values (NAVs) within the […]

France’s EU Council Presidency to focus on new growth model

As part of its rotating Presidency of the EU Council for a six-month mandate, France chaired its first EU Council of Finance Ministers (ECOFIN) meeting on 18 January with a view to getting certain current legislative work finalised. The ECOFIN meeting was mainly dedicated to introducing the Presidency’s roadmap for the months to come. Beyond […]

Positive behavioural and cultural change: the implementation of an accountability framework

As regulated entities execute their post-Brexit strategies and relocate their European Union (EU) operations from the UK to other EU states, a key issue to be addressed for those relocating to Ireland remain to be the impending legislative changes surrounding increased accountability standards for executives and non-executives. Not least, the breaking of the participation link, […]

The long road to proportionality in prudential regulation and supervision

The great financial crisis triggered a massive wave of bankruptcies in the worldwide banking sector, affected not only large international banks such as Lehman Brothers but also local ones such as Northern Rock in the UK. Basel prudential standards are designed to cope with financial risks stemming from the global banking system without taking into […]

Quarterly SSM briefing: spotlight on supervisory priorities, banking union and liquidity ratio

Supervisory priorities 2022-2024 In December 2021, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the national supervisory authorities of the Eurozone countries published their supervisory priorities for 2022-2024. The three-year coverage enables the ECB banking supervision to achieve good progress in addressing the identified vulnerabilities while at the same time affording enough flexibility in any corresponding actions […]

The imperative of expanding the traditional MRM function

Financial institutions and non-bank financial technology companies (FinTechs) alike make extensive use of various machine learning models (MLOps) in core and non-core areas of their business. Banks, for example, rely on such models for a range of risk assessments, including predictive underwriting, credit risk management, suspicious and/or fraudulent activity management, fair lending compliance, derivative and […]

Can banks balance the opportunities and challenges of digitalisation?

The Covid-19 pandemic has amplified technology’s impact on the banking sector, helping to prove that technology now stands at the core of business sustainability for banks. In their constant search for convenience, digitally-savvy customers have pushed banks’ focus towards providing global business solutions more than ever. A new normal has emerged: an environment where banks’ […]

New European authority aims to strengthen framework to fight money laundering