ECB interview: 2025-2027 ECB supervisory priorities and 2025 stress test

ECB interview: 2025-2027 ECB supervisory priorities and 2025 stress test

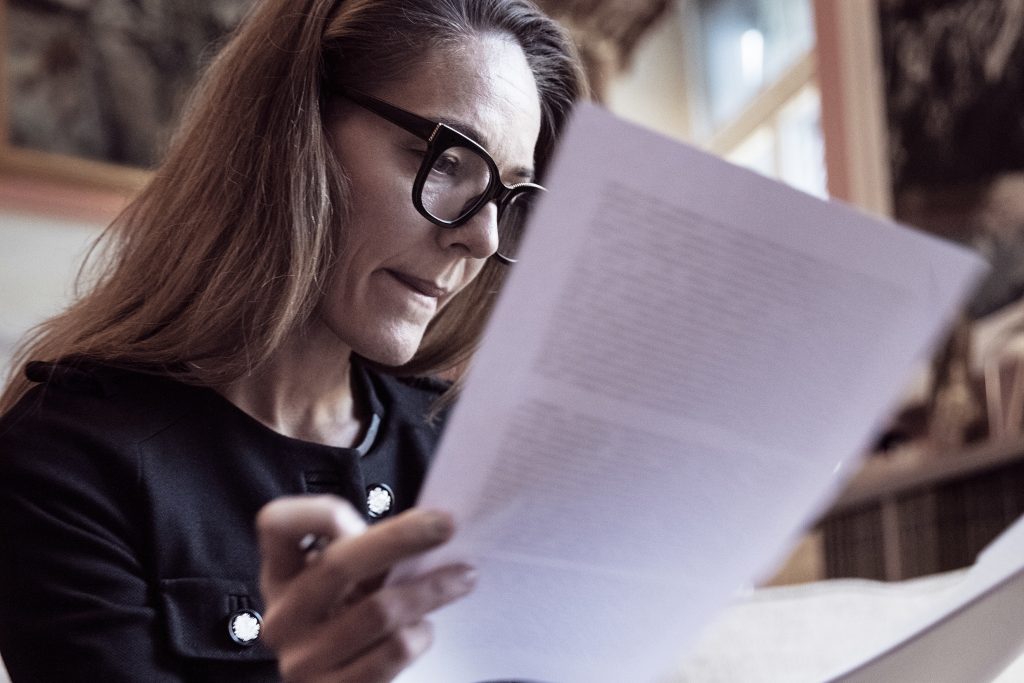

In this exclusive interview by Forvis Mazars, Patrick Montagner, member of the ECB Supervisory Board, discusses the ECB’s supervisory priorities for 2025-2027 and the 2025 stress test. The conversation highlights how the ECB is adapting its supervisory focus and practices to address the evolving risks faced by the banks it supervises, including geopolitical shocks, climate change, and digital transformation. It offers critical insights for banks as they align with the ECB’s evolving expectations, while also emphasising the potential supervisory measures to address severe deficiencies.

Start of ECB transcript:

Interview with Forvis Mazars on the ECB’s supervisory priorities and 2025 EU-wide stress test

Interview with Patrick Montagner, Member of the Supervisory Board of the ECB, conducted by Eric Cloutier, Group Head of Banking Regulations at Forvis Mazars

The ECB’s supervisory priorities for 2025-27 provide banks with critical insights into what will be expected of them over the next three years as they navigate evolving risks and vulnerabilities in today’s uncertain environment.

While the priorities clearly outline the context and set expectations, they also highlight key areas that warrant further examination to fully understand the implications for banks and their operations. I look forward to exploring some of these aspects with you in more detail.

To address potential shocks from the volatile global environment, the ECB introduced a special focus on managing geopolitical risks in its supervisory priorities for 2025-27. Given the cross-cutting nature of these risks, how does the ECB plan to adapt its practices and focus its activities to tackle these challenges effectively? To what extent are banks expected to consider scenario planning in their approach?

The cross-cutting nature of geopolitical shocks necessitates incorporating a special focus on banks’ abilities to manage these challenges in our priorities. While geopolitical risks themselves are not new, the intensity of the shocks and the increased interconnectivity of the world mean banks must reassess these risks and incorporate them in their liquidity and capital planning. This is particularly important when designing stress test scenarios. We can’t assume the world is in a normal state.

Adequate internal governance is essential. Banks must be aware of opportunities to actively manage these risks across different areas. For instance, the Russian invasion of Ukraine did not only impact banks who are present in Russia. Supervisors asked these banks to leave the Russian market and some managed to do so. The rest of the banking sector faced indirect consequences of the conflict in Ukraine such as the macroeconomic impact of the gas crisis. Therefore, banks need to be both proactive and reactive.

Geopolitical uncertainties have increased significantly over the past decade and have intensified in recent years. Banks must be prepared to swiftly address the consequences of a changing geopolitical landscape.

We aim to focus on banks’ risk management processes so that we can identify sound practices and further clarify our supervisory expectations in this area. To do this, we will harness the outcomes of previous supervisory activities and the information gathered by Joint Supervisory Teams (JSTs) throughout their engagement with banks. Moreover, geopolitical risks will be a key component of the 2025 EU-wide stress test.

Looking more broadly, many emerging and novel risks – such as those related to geopolitics, climate, technology and demographics – are longer-term in nature. How is the ECB planning to adapt its current business models and supervisory practices to address these risks?

First, let me clarify that we don’t see these risks as entirely novel. For instance, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change was established 40 years ago, stemming from discussions in the 1970s about the consequences of a changing climate. We have seen both the risk and its intensity accelerate in the past decade, perhaps more rapidly than expected, but the risk itself is not new.

Similarly, geopolitical risks are not unprecedented. In the late 1970s, there were significant events like the Cold War in Europe and in the 1990s there were conflicts in Iran, Iraq and Kuwait. Although we experienced a relatively quieter period afterwards, such risks have always been present.

How these risks are evolving, however, is concerning indeed. Take climate change, for example – and, with the recent wildfires in California and flooding in Valencia, it is an all too pertinent one. We know about the huge costs of reconstruction after these kinds of major climate events. These events do not only have an impact on banks’ lending portfolios; they also have serious implications for the insurance sector, leading to rising insurance costs and a widening protection gap, as several reports and the European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority (EIOPA) dashboard indicate. As such climate events become more frequent, we can’t rely solely on public aid to fill this gap and sustain these costs in the long run.

As supervisors, we must also evolve to be able to adapt to the evolving risk landscape. We need to assess risks as they currently are, not as they once were. This is why we aim to reassess our processes after ten years of European banking supervision. One of our main goals is to adapt the Supervisory Review and Evaluation Process (SREP) by reducing its duration from one year to a maximum of nine months. We started implementing these changes to the SREP at the end of 2024 and they will be fully effective from 2026.

On top of this, we are adopting a multi-year approach within the SREP, which allows us to focus on different aspects over time rather than attempting to cover everything annually. This approach was necessary when European banking supervision was set up, to have a comprehensive understanding of all risks across the EU. Now, however, we must tailor our approach to the specificities of individual banks and the variations in the risks they face.

We also recognise the need for more supervisory tools to address these evolving risks, especially in areas where some banks still demonstrate substantial deficiencies that need to be remediated. Capital requirements alone are not sufficient. As part of the follow-up of on-site inspections, we now aim to issue qualitative and quantitative requirements to tailor our supervisory response to each bank. We will also be using the full range of our supervisory toolkit, following our escalation mechanism to appropriately address the severity of any shortcomings. This may include sanctions and enforcement measures, such as imposing periodic penalty payments (PPPs)[1].

As sound risk management starts at the top, tackling deficiencies in the functioning of banks’ management bodies has been a longstanding focus of the ECB. Bank failures in recent years have underscored the importance of robust internal governance, and, in particular, a strong risk culture. Will the ECB apply greater pressure on banks in this area?

The importance of sound governance is not new. Reflecting on past events like the 2008 financial crisis, it’s evident that any business model – whether a retail bank, a savings and loan institution, an investment bank or a specialised lender – can experience failures. The key differentiator is governance, which starts with strong leadership from the top.

And back in 2014, for example, the Supervisory Intensity and Effectiveness group of the Financial Stability Board (FSB) emphasised the importance of robust board involvement. Board members must be actively engaged, capable of collectively assessing risks, evaluating the performance of internal functions and ensuring accurate reporting.

To emphasise our expectations in this area, we conducted a public consultation on a draft ECB Guide on governance and risk culture last year[2], and we are currently in the long process of assessing the comments received. The final version of the Guide will be approved by mid-2025. The Guide aims to provide clarity on our supervisory expectations and ensure we are understood, so that banks can respond accordingly. In our role as supervisor, we want to foster a better risk culture in banks to ensure they can manage risk at any point – as risks may materialise at any point in their life cycle. We emphasise the need for boards to have clear risk, internal audit and finance functions. We also need a board that functions correctly and is collectively well-equipped to address all these risks.

Diversification, including gender diversity, is therefore important. Often, we see homogeneous board members with the same culture, lacking diverse perspectives. Many countries lack clear incentives for this. We also need diverse skills among board members to effectively handle IT risks, credit risk and other challenges as they arise. We will continue to push for improvements where necessary. But we of course don’t aim to impose a unique model; each bank has its own business models, roots and traditions. However, the internal risk culture must adapt to the business model, which is not always the case, as some banks mistakenly assume that a successful business model in the past will remain so indefinitely. But times have changed.

Addressing deficiencies in credit risk management frameworks remains central to the ECB’s priorities, especially in the current environment of high uncertainty. While many activities defined in the priorities build on past efforts, what new measures or shifts in focus should banks expect this year regarding credit risks?

Credit risk remains central to our supervisory assessment of banks, though it varies across different areas such as consumer loans, mortgage loans, loans to small and medium-sized enterprises, leveraged finance and real estate. We focus on credit risk in a broad manner, but also conduct deep dives into specific areas. In some sectors, risks have increased due to changes in the interest rate environment, making certain past transactions more vulnerable than anticipated.

Thus, while credit risk is our core focus, we are particularly concerned with specific areas that are more exposed. We devote substantial resources to this assessment and strive to understand how these “novel risks”, like geopolitical or climate and environment-related risks, can also affect the traditional risk categories. For instance, to build on my previous example, the recent floods in Valencia led to defaults among small and medium-sized enterprises and individual borrowers, resulting in losses for banks.

Consequently, supervisors continue to apply credit risk measures that vary across different banks. Banks with different business models or those exposed to specific countries will need to account for varying levels of credit risk. We are therefore tailoring our approach each cycle, to ensure we remain flexible and can adapt to the evolving risks in banks’ lending portfolios and collateral.

Operational resilience also continues to be a critical area of focus. With the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) applying from 17 January 2025, how does the ECB plan to practically assess significant institutions’ compliance with these new requirements? Additionally, how will this align with the ECB’s planned activities for operational resilience, particularly in managing third-party service providers?

Operational resilience has long been part of regulation; the concept of business continuity planning has always been present. The cost of protection against external attacks – or even internal mistakes – must be considered, as increasing IT integration increases the risk of IT-related issues. While resilience isn’t a new concept, there is now a new framework in place and we expect banks to allocate dedicated and sufficient resources to ensure they comply with DORA requirements.

First, the European Supervisory Authorities (ESAs) will need to identify and assess third-party critical providers.

As part of our regular supervisory activities, we will evaluate banks’ compliance with DORA, including, among other things, the assessment of their digital operational resilience. We will also introduce a new supervisory tool, threat-led penetration testing, which, while not entirely new in all countries, was previously done more informally without clear legislative rules. We may not apply this to all banks, but will focus on the main risk areas and key actors at the outset.

Overall, implementing DORA is an important task for everyone involved – both for financial actors and the broader community of supervisors, including the national competent authorities (NCAs) and the ESAs.

Banks’ ability to adequately manage climate-related and environmental (C&E) risks remains a high priority. What supervisory activities can banks expect, now that the expectations outlined in the ECB Guide on C&E risks should be fully implemented and in the light of the additional requirements introduced in the new CRR3/CRD6 banking package?

Now that the deadline set in our Guide on climate-related and environmental risks[3] has passed, supervisors will work to follow up on the measures which banks should have now adopted to be in full alignment.

Effectively, CRD6 has created new requirements for banks and supervisors, including the need for transition plans, and we will integrate the assessment of these plans in our own supervisory process. Prudential transition plans will be reviewed when the European Banking Authority (EBA) guidelines become applicable. It’s crucial to have a thorough assessment of these plans, as it’s our first year evaluating them, making it a learning experience for the supervisors.

The FSB recently published a report on the relevance of transition plans, noting that the methodology currently remains unclear and fragmented.[4] We will make sure banks are able to update their transition plans with accurate and granular data. But both banks and supervisors need to stay informed and enhance their knowledge. We aren’t scientists, so we need to allocate time, people and resources to fully understand these evolving transition and physical risks – as well as the evolving information about them.

Climate change and the risks it brings can take different directions under various scenarios, all of which must be evaluated carefully for both the short and long term. Transition planning is very important for this. I recently read an article in the Financial Times[5] which discussed the potential consequences of global warming, one of which could be a colder northern Europe. This scenario might occur if the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) – a vital part of the ocean circulation system which sustains the Gulf Stream – were to collapse. Without the Gulf Stream, countries with continental climates, such as the United Kingdom, France and Germany, could experience much harsher winters. With that being said, this remains a possibility rather than a certainty; there are limited data to predict if or when it might happen, also given the Gulf Stream’s complexity and unpredictability. Nonetheless, it is crucial to address these uncertainties and stay up-to-date with the latest data and research.

The point of insurance coverage I mentioned earlier is also important, as it affects banks’ risks and lending strategies in the longer term. If insurers refuse to cover certain areas, this is a problem for banks. If a lender issues mortgage loans but can’t find an insurance company that covers floods, and a climate-related event occurs, both the bank and its client would suffer financial consequences. According to EIOPA, a significant protection gap exists in some countries due to the unavailability of home insurance in certain areas[6]. Additionally, insurance is not mandatory in some countries. Banks, especially the ones operating across jurisdictions, must therefore be mindful of these challenges.

At the ECB, we understand the importance of climate risk and have been proactive in this area. We believe that denial is not an effective response to the challenges of climate change.

Can you please elaborate on the planned deep dives into banks’ ability to address reputational and litigation risks related to C&E commitments?

We issued supervisory expectations on C&E risks to banks, including on reputational and liability risks, and are currently reviewing the documentation that was submitted. We have made it very clear that new delays won’t be tolerated, as the ECB already granted an extension of the initial deadline in some banking groups last year.

Our deep dive into reputational and litigation risk is ongoing, involving a limited number of banks. We will carefully assess the outcome and plan to communicate our findings to banks in the coming months. Our intention is to identify good practices and share them with the industry. This process is extensive, as supervisors need to evaluate several factors and look at a significant amount of information.

Banks are already doing their own research about the potential impacts of climate risks on them and their business models. The growing trend of climate-related litigation, which has increasingly been affecting financial institutions, has become a significant concern in recent years, as highlighted in reports by the Network for Greening the Financial System. The main legislative frameworks, including the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (BCBS) principles and the EBA guidelines, underline the growing importance of addressing climate-related litigation and reputational risks within the banking sector. Seeing as banks play such a crucial role for the economy, they are under public scrutiny, and reputational and litigation risks must be carefully evaluated. These kinds of risks could arise if banks fail to meet public or regulatory expectations on environmental issues.

Many banks remain non-compliant with the BCBS239 principles, more than a decade after their introduction in 2013. In May 2024 the ECB published its Guide on effective risk data aggregation and risk reporting, setting clear expectations for banks. What new supervisory measures and enforcement actions does the ECB plan to implement to address persistent deficiencies?

Despite our efforts, deficiencies persist, particularly in risk data aggregation and reporting. Sometimes, poor management information systems are caused by inadequate IT infrastructure, but more often, this issue arises due to a lack of timely and accurate data. Information loses its value if it’s delayed or unclear. Therefore, a good management information system must continuously evolve with the changing environment.

We are intensifying our focus on improving risk data aggregation to ensure banks can effectively address growing risks. It isn’t just at the ECB level that this effort is being made; NCAs have also highlighted the importance of timely, accurate information, for example the Banca d’Italia in a recent statement on less significant institutions and the French Prudential Supervision and Resolution Authority in its annual report. While these issues aren’t new, significant progress needs to be made. Banks with ongoing deficiencies should expect increased pressure from the ECB to enhance their data aggregation and risk management capabilities.

In general, if banks fail to address persistent deficiencies, supervisors will use the full range of tools and powers available to them, including PPPs. This enforcement measure is an integral part of our supervisory toolkit and is applied in line with the principle of proportionality. It can help us address different kinds of problems, as capital requirements are not the solution for everything.

Priority 3 emphasises the need for banks to strengthen their digitalisation strategies and address challenges arising from the use of new technologies. What are the ECB’s key concerns in this area? Additionally, could you explain how the ECB plans to assess the impact of digital activities on banks’ business models and associated risks?

We have evaluated the digitalisation activities of over 20 banks and published a report last July to share our findings and best practices.[7] While supervisors do not intend to impose a singular business model, it is evident that digitalisation has become an essential expectation from customers, whether they are treasuries, firms, or individuals. Despite the varying degrees of digital adoption, banks will ultimately need to embrace digital solutions. Digitalisation provides new opportunities but also brings risks, as poorly managed implementation can leave systems vulnerable to threats like hacking.

The EU banking sector operates according to one single rulebook, yet it is not a fully unified market due to factors like language barriers, which add additional costs for global players. We believe that enhancing efficiency through IT and digital investments is vital for the sector’s future. However, digitalisation is challenging, as it requires substantial investment and innovative approaches, and it is still in the early stages for some banks. Banks are cautious about artificial intelligence too, but they will eventually need to explore its potential to boost efficiency and improve their cost-income ratio.

Investment in digitalisation and IT is crucial for increasing banks’ efficiency at EU level, enabling them to compete with new entrants who are free from legacy IT constraints and often enter the market through specific segments like payments. This presents a challenge for traditional banks, which must balance IT expenses while facing competition in profitable areas.

Understanding and implementing new technologies, along with assessing the associated risks, is essential. Although discussions about AI are not new, the ability of modern IT systems to quickly process large volumes of data is a recent development. Banks are using new technologies to refine internal models and designs, but these improvements hinge on accessing high-quality data, a challenge faced by all financial actors.

At the ECB, we employ AI to boost our efficiency, streamline our work and manage the multitude of files we receive. Many NCAs have also developed internal tools and supervisory technologies. These initiatives span various areas such as enhancing analytical capabilities through AI tools like Athena, facilitating collaboration and digital exchange with our Virtual Lab, and integrating core systems with projects like Olympus to create a unified supervision cockpit. This approach is beneficial for us and helps us understand the challenges faced by the banking system, as we encounter similar issues.

The ECB and EBA have launched the 2025 EU-wide stress test, which is conducted every two years. What is the 2025 EU-wide stress test about? What is its aim? And why are you conducting a scenario analysis on counterparty credit risk in parallel?

The euro area banks taking part in the EU-wide stress test, which is being coordinated by the EBA, are selected so that the test covers roughly 75% of banking assets in the euro area. To be included, banks need to have assets totalling at least €30 billion. For directly supervised banks that are smaller and thus excluded from the EBA sample, the ECB carries out its own stress test exercise. The objective for both samples is to examine the capital position these banks would develop over the next three years until the end of 2027, under both a baseline scenario and an adverse scenario.

The results will serve as an output for the SREP assessment. We will use the results of the stress test to assess the Pillar 2 capital needs of individual banks. The qualitative outcomes will be included in the risk governance part of the SREP, so will potentially influence the determination of Pillar 2 requirements. The quantitative results will be used as a key input for setting the Pillar 2 guidance and the leverage ratio Pillar 2 guidance.

In addition to this, we are going to conduct a scenario analysis of counterparty credit risk. It is not part of the EU-wide stress test but will be run broadly in parallel with it. It is a deep dive into banks’ counterparty credit risk exposures to non-bank financial intermediaries and aims to follow up on some deficiencies in stress test practices identified by the ECB in targeted counterparty credit risk reviews.

However, I’d like to underline that it is not just the results of these exercises that matter; the discussion between banks and supervisors is also important. Moreover, while stress testing by supervisors serves as a tool for dialogue, it is also a useful tool for banks’ own purposes. It acts as an internal tool, providing an idea of what might happen – essentially, a “what if” scenario rather than an absolute truth.

Do you have any additional points to draw attention to or key concluding messages you would like to share regarding the ECB’s supervisory priorities for 2025-2027, or the upcoming stress test?

As a supervisory authority, our primary focus is risks. Risks are dynamic and ever-changing, and since a bank’s business model inherently involves taking risks, it’s imperative for them to assess and reassess these risks daily. Our role is not to prevent banks from taking risks, but to ensure they fully understand them and can manage them effectively. Therefore, both banks and supervisors must stay up to date with the latest developments and data to effectively manage and mitigate these risks.

For us as supervisors, it is essential to remain vigilant and proactive in our approach. In the 2025-27 supervisory cycle, we will focus on using the full range of our supervisory tools to ensure that banks address any deficiencies promptly and effectively. As I mentioned earlier, should banks fail to do so, we are prepared to employ our tools, which include binding quantitative and qualitative supervisory measures, sanctions and enforcement measures such as PPPs.

PPPs can be used by the supervisor if a bank fails to comply with a supervisory requirement to tackle any prudential risk that is not properly covered and managed. There is a specific methodology for calculating these penalties, which considers the severity of the non-compliance and the size of the bank. While not a sanction, these penalties serve as an effective tool in situations where banks have not adhered to supervisory guidance. We must ensure that when we require banks to implement certain remediation measures, they actively follow through. If they do not, it raises important questions about the implications of their inaction.

[1] PPPs require the bank to pay a daily amount for every day that it is in breach, for a maximum of six months; [2] ECB (2024), Public consultation on the Guide on governance and risk culture; [3] ECB (2020), Guide on climate-related and environmental risks – supervisory expectations relating to risk management and disclosure, November; [4] Financial Stability Board (2025), “The relevance of transition plans for financial stability”, 14 January; [5] Financial Times (2025), “The utterly plausible case that climate change makes London much colder”, 11 January; [6] The ECB and EIOPA have recently issued a joint paper making a proposal for an EU-wide approach to reduce this gap. See ECB (2024), “ECB and EIOPA propose European approach to reduce economic impact of natural catastrophes”, press release, 18 December; [7] ECB (2024), Digitalisation: key assessment criteria and collection of sound practices.

End of ECB transcript

Read more from Forvis Mazars on the latest regulatory and supervisory developments

- Subscribe and read our quarterly global FS regulatory insights newsletter from our Global FS Regulatory Centre

- The rising importance of risk culture in banking supervision

- NGFS climate risk scenarios: Implications for financial institutions

- Growing global regulatory emphasis on banks’ third-party risk management

- EU banks to rapidly improve their risk data capabilities.

- Operational resilience: where do we stand and what does this mean for cross-border banks? | Let’s talk financial services