Perspectives | 29 September 2016

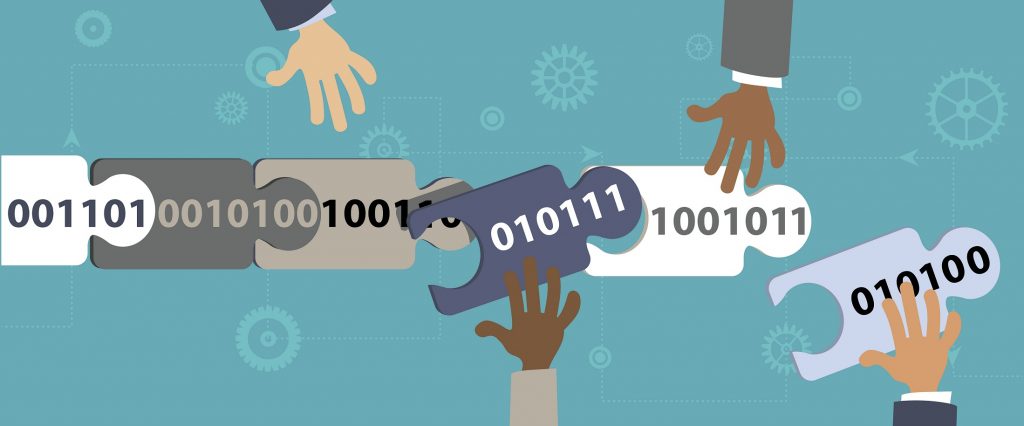

“Blockchain is a bit like gluten. Everyone is talking about it, but no one knows what it is,” said Tim Swanson, head of research at R3, the financial technology innovation firm that is leading a consortium partnership working on blockchain to develop industry-wide common practices and standards, architecture models and specific transaction systems for use in global financial markets.

Blockchain is part of the technology behind digital transactions such as bitcoin but can be used for a range of transactions. It can either be a private or public digital ledger of transactions, agreement and contracts. R3’s blockchain model is private and its governance is controlled by the consortium. Whereas with a public blockchain, where access is completely free, “code is law”.

The governance of blockchain raises significant questions of responsibility and regulation: who is responsible or liable in the absence of administrators? How can the legitimacy of activities be managed and ensured?

According to Kramer-Levin partner Hubert de Vauplanne: “In so far as both public and private chain operations cross frontiers, the methods of determining this system of proof can only be developed through an international agreement. In the absence of an agreement, there is the danger that legal control of the blockchain will be seized by a state power stronger than the rest. The precedent of the Internet and the legal control exercised by the US should serve as an example. This risk of loss of sovereignty is a real risk that cannot be ignored.”

It is crucial, therefore, to establish a new legal framework in order to fully realise blockchain’s benefits and recognise potential dangers, while nevertheless embracing all the areas in which it can be exploited. We must also take care not to hamper its potential by restricting it to traditional and ill-suited legislation.

In response to the concerns that have been raised, the European authorities are starting to take notice. Recently, the European Parliament endorsed the report delivered by Jakob von Weizsäcker, recommending that blockchain should be regulated proportionately and pragmatically. In France, there has been the Sapin 2 law on the use of blockchain for unlisted securities and for mini-bonds in the crowdfunding sector.

For CNRS and Harvard researcher Primavera de Filippi, “the benefits of a decentralised technology can only be fully exploited if we succeed in bringing it under a decentralised form of governance.” In this context, we may legitimately ask questions about the suitability of R3’s centralised governance for decentralised technology.

While R3’s proposals seem attractive in terms of governance, regulation and responsibility, we may ask whether such an approach will see the full potential of blockchain being exploited. Particularly as one of the main benefits of blockchain lies in the total disintermediation of transaction flows, whereas R3’s blockchain is aiming to develop into a new type of intermediary (a trusted third party) replacing stock markets, banks and brokers.

The structure of decentralised organisations also made it difficult to make decisions, particularly key choices that ensure they remain sustainable. In May 2015, bitcoin suffered its first major security breach. This was mainly because the bitcoin community had failed to take decisions to develop its protocols. How can we have confidence in a style of governance that is unable to make decisions required to ensure its own sustainability?

Further, decentralised collaborative applications could develop in an even more independent manner, eliminating not just the intermediaries but the administrators too. These independent decentralised organisations would be managed by blockchain-based software. We need to be very wary of an organisation managed solely by machines.

There is no doubt that blockchain could soon make it possible to change how transactions are conducted between financial players. But in order for blockchain to develop sustainably, we must study its ecosystem, working together with all the stakeholders. That will enable us to escape the vicious circle of decentralised or disruptive technologies which trigger increasingly severe regulation as authorities struggle to adapt, prompting the technology to become even more decentralised and disruptive in turn.

See also:

Data governance : the key to reconciling contradictory requirements